A guest post from network member Dr Beatrice Groves, of the University of Oxford.

Beatrice’s latest book, The Destruction of Jerusalem in Early Modern English Literature, has just been published by Cambridge University Press. Among many topics examined in the book, one chapter focuses on the siege of Jerusalem in the work of Shakespeare. Perhaps Shakespeare’s most famous reference to Jerusalem is his depiction of the death of Henry IV in the Jerusalem chamber at Westminster Abbey, a scene discussed by Beatrice below:

Like the author of a recent network blog, I was lucky enough (while a friend was instituted as a canon) to visit the Jerusalem chamber this year. Following on from this, I thought I’d write about an ironic aspect of Henry IV’s death in this chamber which I noticed when I looked above my head and which has not, to my knowledge, been previously noted.

Henry IV’s death in the Jerusalem chamber is most famously described in Shakespeare’s Henry IV part 2:

It hath been prophesied to me, many years,

I should not die but in Jerusalem,

Which vainly I suppos’d the Holy Land.

But bear me to that chamber; there I’ll lie;In that Jerusalem shall Harry die. (4.5.236-40)

The word ‘vainly’ is Henry’s caustic acknowledgement that while he had believed he had many years to live he has now discovered that, through an accident of naming (and no-one now knows why this room is called the Jerusalem chamber) he has only hours before he will die. In Holinshed – from whom Shakespeare takes this account – the king takes it slightly differently:

they bare him into a chamber that was next at hand, belonging to the abbat of Westminster, where they laid him on a pallet before the fire, and vsed all rememdies to reuiue him. At length, he recouered his speech, and vnderstanding and perceiuing himselfe in a strange place which he knew not, he willed to know if the chamber had anie particular name, wherevnto answer was made, that it was called Ierusalem. Then said the king; “Lauds be giuen to the father of heauen, for now I know I shall die heere in this chamber, according to the prophesie of me declared, that I should depart this life in Ierusalem”.

Offering ‘Lauds’ to God, Holinshed’s king seems to gain some kind of comfort from the knowledge that he will die in the Jerusalem Chamber (as Shakespeare’s Henry does, belatedly, in his more affirmatory final line: ‘In that Jerusalem shall Harry die’).

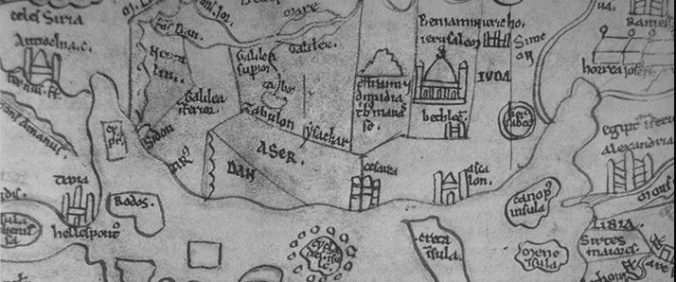

Our fellow network member, Anthony Bale, has written on his blog Remembered Places that many kings sought to die in Jerusalem. Henry’s death in the Jerusalem chamber is one link in his long project of associating himself with the Holy Land and its legitimating aura of sanctity. When Henry IV was still merely Harry Bolingbroke, he had taken a pilgrimage to Jerusalem (and he had done it properly: records suggest that he followed the pious custom of travelling the final forty miles from Jaffa on foot). Bolingbroke retained this respectful attitude towards the Holy Land when he came to be crowned, for his coronation is the first definite record we have of an English coronation taking place on that most contentious royal relic, the Stone of Scone.[1] In contemporary discourse the Stone of Scone is virtually synonymous with Scottish nationalism (its return to Scotland in 1996 was watched by 10,000 people who lined the Royal Mile) but this has obscured another aspect of the stone. When it was taken from Scotland by Edward I it was not only the site of coronation for Scottish kings but also a major relic from the Holy Land. It was believed to be – as noted by a chronicler in 1292 – ‘the stone on which Jacob had rested his head’ at Bethel (Genesis 28:10-22).[2]

The English monarchy has long been drawn to relics from the Holy Land. Henry IV’s coronation on the Bethel Stone has been followed by English royalty ever since, and when Charlotte Elizabeth Diana Windsor was baptised this year with water from the River Jordan she was following in a royal tradition, which, it is claimed, ‘dates from the Crusader king Richard I’ (Majesty, 5.9 (January 1985): 17). This ancient and persistent royal habit is due to the legitimising aura of holiness conferred by such relics and this aura was, of course, particularly necessary in the case of Henry IV. Henry IV was probably the first English king to be crowned seated on the Bethel Stone because his usurpation of Richard II’s crown meant that he needed all the symbolic legitimacy he could muster.

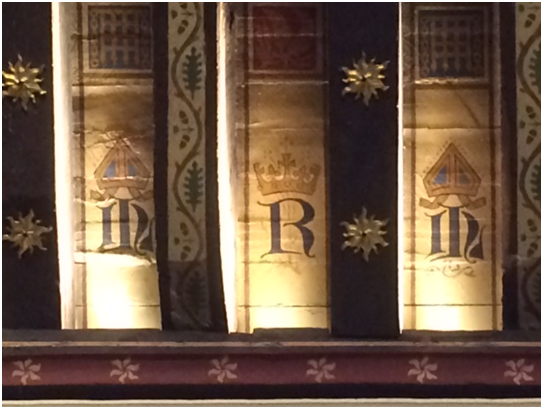

Henry IV, therefore, both began and ended his reign in (or on) the Holy Land: crowned on the Bethel Stone and dying in the Jerusalem chamber. But there is also a further circularity here. Henry IV needed the Bethel Stone at his coronation because his claim to the throne was a little shaky given that he had deposed and murdered Richard II, and Richard II was symbolically present at his death likewise. The Jerusalem chamber was built during Richard II’s reign and the ceiling is one of the few aspects of its original interior that remains. Had Henry IV looked up as he lay dying he would have seen (alongside the mitred initials of Abbot Nicholas Litlyngton) a ceiling richly decorated with the crowned ‘R’ of Richard II and emblazoned with the golden suns that were Richard II’s emblem.

Henry’s death in the Jerusalem chamber involves a certain irony given that the king believed he would die in the Holy Land; had he noticed Richard II heraldically triumphant above him, Henry himself might have found his death in this room even more pointed than subsequent generations have thought it.

[1] Johannis de Trokelowe and Henrici de Blaneforde, Chronica et Annales, Regnantibus Henrico Tertio, Edwardo Primo, Edwardo Secundo, Richardo Secundo, et Henrico Quarto, ed. Henry Thomas Riley (London: Longmans, Green, Reader and Dyer, 1866), p. 294.

[2] Willelmi Rishanger, Chronica et annales, regnantibus Henrico Tertio et Edwardo Primo : A.D. 1259-130, ed. Henry Thomas Riley (London: Longmans, Green, Reader and Dyer, 1865), p.135