By Dr David Landy, Trinity College Dublin.

The ‘City of David’ is an illegal Jewish settlement in Silwan in East Jerusalem. As such it is a place of violence and tension, with local Palestinian resistance to their colonisation met with brutality by settlers and the Israeli authorities.

David Be’eri, settler leader, drives his car into a stone-throwing Palestinian child in Silwan October 8, 2010. Photo by: AFP

Strangely, it is also a popular tourist spot with hundreds of thousands coming to see the archaeological dig there, as this was the original site of Jerusalem. I visited the site in order to find out how tours of the site portray local Palestinians. It has been claimed that Palestinians are erased in these tourist narratives, mirroring the de facto erasure practiced by the Israeli settlers who guide tourists around.

While this was one way Palestinians were dealt with, there were times when tours could not elide over their presence. For instance, when tours pass this ‘look-out point’, we were offered a panoramic view of part of Silwan. Row upon row of Palestinian houses were laid out before us, and it was impossible to ignore them.

How then were they dealt with?

The ‘look-out point’ in the City of David. Note the military terminology the site uses.

Below is an anecdote from a tour I took. It illustrates one way Palestinians are narrated. On this tour, the Israeli tourguide used the place to tell us about the walls surrounding ancient Jerusalem. She chose a girl of about 12 or 13 from the mostly Jewish audience as a ‘volunteer’ and said ‘meet the hill on which we will build the City of David’.

Pointing to the girl she asked us, ‘If you are to defend your city, where would you build the walls?’ When someone correctly answered ‘high up’, she instructed the girl to raise her hands over her head as ‘walls’, something which made her look even more vulnerable, in need of protecting.

The guide then explained that we also need to protect the water source of our city, at the bottom of the hill, around the girl’s legs. Then she added, ‘we can’t build the walls low down around her legs because if we did, then the enemy on the other hill…’ – and here she pointed to where the Palestinian houses on the other hill were crowding along the slopes, and everyone’s gaze followed her finger and they nodded in understanding. ‘Then the enemy on the other hill, they would fire into her stomach’.

At the time, I was shocked by the visceral atavistic images this narrative evoked, the young woman on whom we build our Jewish city, the need to defend our vulnerable young (Jewish) women, and the casual relegation of un-named Palestinians to the role of the inevitable enemy threatening our citadel. It was a narrative which both elided over Palestinian presence and treated it as a threat.

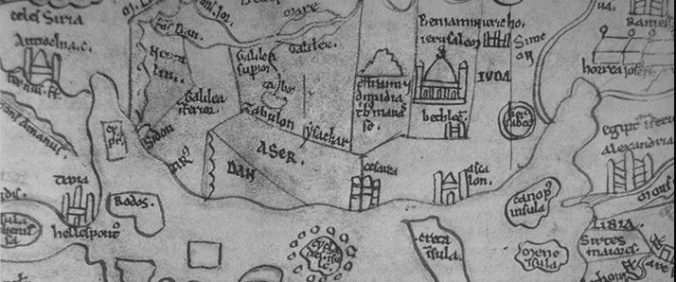

The imagined ancient ‘City of David’.

In retrospect, the fact that nobody else was shocked was of equal interest. For key to narrating Palestinians as the enemy is doing so in a non-political, naturalised way which all could accept. And key to the naturalisation process is the sublimation of this enmity.

After all, the tourguides (and while on the lookout point I observed several guides doing the same thing, pointing to the Palestinian houses to illustrate the need to and the ways of defending the City of David) were only discussing ancient history. Palestinians were not named, were not mentioned. This rhetorical trick reminds me of how two of racism’s main carriers are the joke and the rumour, both modes of expression that allow the speaker to disavow the racism they are enunciating, as well as representing it as a commonsensical way of understanding of the world.

In like form, in this tourist site, such stories of ancient city walls protecting the citadel from enemies on neighbouring hills were used to make sense of the confusing ruins we were walking around in. But they had another purpose: these past stories of militarised history served to sublimate the present-day violence against the Palestinians in Silwan. Palestinians themselves were treated as ghosts, absent presences who were faintly threatening, from whom we, in our Jewish citadel, were presently safe.